Image source: medium.com

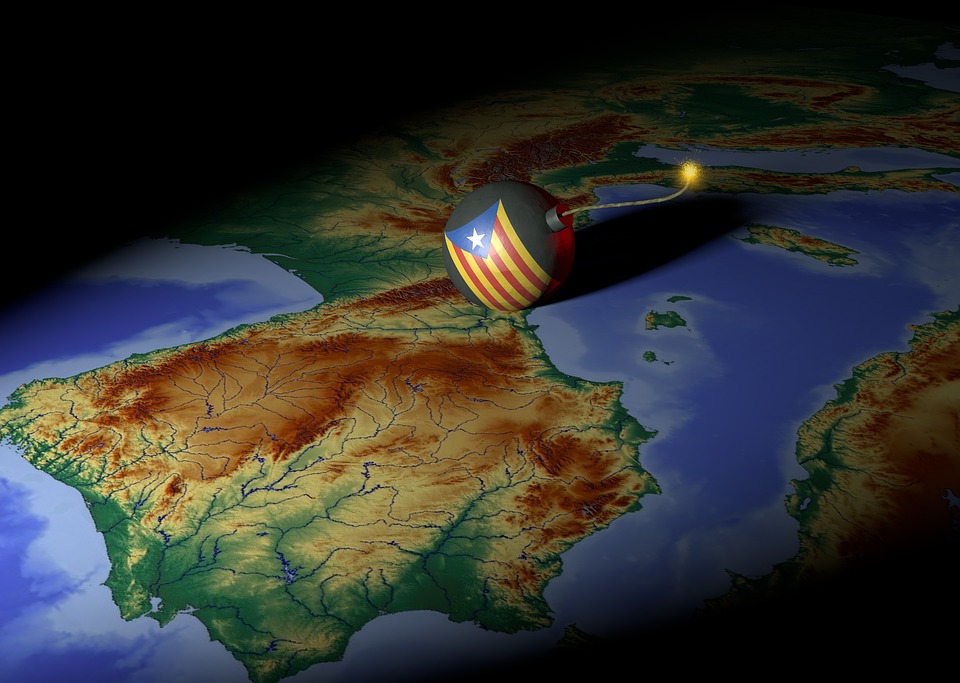

The Catalan Crisis is a matter of national identity. To be more specific, the crisis started with the wish of having the Catalan identity recognized as unique and indisputable by the Spanish central government in Madrid. Non-recognized pro-independence Referendums were organized within the 2009-2011 timeframe, but the apogee was met in 2017. However, the strong longing for independence is not new. Catalans’ requests to be known as a distinctive nation within Spain, being able to posses their own independent political and economic power, have been playing an important role for their identity. The region developed between the French and the Spanish borders along history. Wars, social, political and economic relations influenced how their unique traditions and customs and language evolved.

Academics and authors have been debating the importance of borders and cultural frontiers in relation with the national identity. One example is Thomas Wilson and his work on ‘Border Identities’. Thomas Wilson focused on the historical formation of the Catalan identity in the Valley of Cherdanya.[1]. He discusses how the conflicts between the two states shaped both sides of the valley from an economic, political-administrative and social points of view.[2] Other authors, like Henry and Kate Miller,analyzed the linguistic component of the distinctive identity. The Catalan language offers a uniqueness to the region and differentiates it form the surrounding territories.[3] Another angle they approach is the matter of Spain as a decentralized state, consisting of 17 regions, among which Catalonia is the richest, paying more taxes to the central government than any other. As a direct result, prominent nationalism has emerged, being conducted by the political elite in the government of Catalonia, the Generalitat.[4]

The Spanish Flag

After General Franco died in 1975 alongside with his authoritarian regime, the level of the Catalan autonomy grew with the Statute of Autonomy under the new Spanish Constitution of 1978. In 2006, a new such Statute was published, and a period of violent pro-independence Referendums started. The apogee of the pro-independence movement conducted by the ruling Catalan political elite took place last 2017, when their leader Carles Puigdemont took the charges and organized a Referendum. Before it could be conducted the Spanish Rajoy government declared it illegal. The pro-independence Referendum for a Catalan Republic was held anyway, followed by interference by the Spanish police. Afterwards, a failed attempt to officially declare the independence was organized by Puigdemont’s Generalitat. Within this period, Carles Puigdemont, observing that his political dream will eventually fade away, began to use a last political tool, his speeches.

Through his words, Carles Puigdemont tried to negotiate with the Spanish government to obtain a better position for his region and to keep the Catalan political project alive. He threatened declaring independence, asked for open discussions between the two sides under the European Union mediation. This political pressure had the purpose of buying some time for gathering the necessary forces to make the political dream of Catalan independence to come true. Eventually, Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy dissolved the Catalan Parliament, arrested and put under investigation Carles Puigdemont and his supporters declaring early regional elections in December. Therefore, an important part of the Catalan autonomy was taken away by the central government and the Catalans remained under the Spanish control. Carles Puigdemont fled the country, but he continued to fight for the Catalan cause using his speeches and asking for justice from the European community.

Catalonia’s next attempt at independence – only a matter of time?

In addition, the EU’s response to Puigdemont’s calls for help and meditation was a neutral one. The European officials have agreed that this conflict is a domestic affair of the Spanish state. Moreover, Donald Tusk advised the Spanish Government to favour the force of the argument, not argument of force[5]. However, EU officials declared that the Referendum was not legal under Spanish law. Thus, the European Commission called for respect of the rule of law, of human rights and having as a purpose unity and not defragmentation. Even though the 2017 attempt of the Catalan region to achieve independence has failed, this does not seem to have dampened the desire of the Catalan people to become a nation of their own. A new campaign for independence seems to be more a question of when rather than if.

Please note that the views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of Munich European Forum e.V.

References

[1]Border Identities: Nation and State at International Frontiers, ed. by Thomas M. Wilson and Hastings Donnan (Cambridge, UK ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

[2] Thomas M. Wilson and Hastings Donnan – Border Identities, 1998

[3]Henry Miller and Kate Miller, ‘Language Policy and Identity: The Case of Catalonia’, International Studies in Sociology of Education, 6.1 (1996), 113–28 <https://doi.org/10.1080/0962021960060106>.

[4]Elizabeth M DeWaard, ‘Catalonia, An (Unhappy) State Within a State’, 23.

[5] Nazaret Romero, ‘Tusk Asks Spanish Government to “Favour Force of Argument, Not Argument of Force”’ http://www.catalannews.com/politics/item/tusk-asks-spanish-government-to-favour-force-of-argument-not-argument-of-force, [accessed 7 September 2018].